The

History of Equestrian Travel

by

CuChullaine O'Reilly

It is only fair to admit up front that I do not feel qualified to

write this article. In fact there is no living expert who can claim

such an honor. This is because the subject of Equestrian Travel is

the forgotten mother of our collective horse scene.

Before there were show rings, or trail rides, or rodeos, or three-day

eventing, or dressage, or jumping, or gymkhanas, or polo ……….

before all of those latter day events, there was equestrian travel.

If I am struggling to explain to you the "why" of its importance,

I can at least adequately explain the "how" of its appearance.

The Institute of Ancient Equestrian Studies has documented a 6,000-year-old

interaction between equines and humanity. Using space-age methods,

these diligent scientists proved that horses were mounted, and ridden,

before the Pyramids were built.

|

For 6000 years horsemen, and women, with bold eyes and dauntless

bearing have overshadowed their earth-bound contemporaries.

|

You

may be saying to yourself at this point, "So what?"

In which case I must direct you back in time.

Johannes Jensen visualized in his book, "The Glacier,"

how mankind might have first cautiously approached, and then mounted,

a wild horse. The world was a new place then. Humanity was obsessed

with the dual daily efforts of survival and food. The horse was

seen as nothing but another source of protein, a tasty, fleet-footed,

chunk of meat not easily delivered to the stone-age dinner table.

Thus we will never know who made the first decision not to view

the horse through the eyes of a predator? The Celts have long cherished

the oral tradition of Epona, a legendary female who could communicate

with and ride horses. Regardless, some skin-clad man or woman, whose

name is now lost in the abyss of time, listened to an inner voice

and changed our collective history. Humanity reached out the hand

of friendship to the wary equine and a new interspecies relationship

was born.

Since then there has never been a more productive bonding of man

and animal.

The horse was soon plowing the ground that nurtured our first hard

won seeds. He helped us round up our scattered flocks. He aided

our scouts to warn us of advancing danger. He even put aside his

peaceful nature and agreed to pull our war chariots to the walls

of Troy.

But more importantly, the horse set us free!

I must admit at this point that I despise walking.

My long-standing motto is that I never willingly walk further than

from the bedroll to the saddle. I am a firm advocate of the ancient

belief that God gave us horses in order to free us from the bondage

of gravity.

And free us the horse did!

For what that first Stone Age horseman discovered still holds true.

Pedestrians stay in their villages.

Horsemen roam the world.

Ask any Long Rider and they will tell you that the world looks different

from atop a horse. No distance is too grand. No desert cannot be

crossed. No mountain cannot be conquered. No river cannot be swum.

No geographic obstacle has ever succeeded in defying the combined

bravery of horse and human. For thousands of years this four-legged

friend has been taking horsemen to places beyond the daily definitions

of dogmatic pedestrians.

Yet it was not always so.

In fact this ancient liberation which the horse brought into our

collective bargain almost ceased to exist as recently as the 1950s.

For a few brief moments in the world's collective consciousness

the legendary candle known as equestrian travel flickered, and was

nearly extinguished by the world's indifference .

To explain this statement let me first tell you about Aime Tschiffely.

He is credited with being the greatest equestrian traveler of the

20th century. Starting in 1925, Aime rode 10,000 miles from Buenos

Aires, Argentina to Washington DC. The book he wrote, "Tschiffely's

Ride" is considered the most important equestrian travel book

ever written. It details the adventures of Aime and his two beloved

Criollo horses, Mancha and Gato. Not only is it an excellent read,

in addition the book inspired four generations of equestrian gypsies

to take to the saddle in search of adventure.

|

|

Legendary

equestrian traveller, Aime Tschiffely, is seen crossing a swinging

rope bridge in Peru, circa 1926 |

The

list of now famous equestrian explorers who were inspired by Aime's

legendary equestrian exploits reads like a "Who's Who"

of nomadic elders.

When John Labouchere rode 5,000 miles through the Andes Mountains

he cited Aime as his inspiration. When Alberto Barretta rode 18,500

kilometers through the wilderness of South America he credited Aime

with the idea. When I rode through the Karakorum Mountains of Pakistan

I offered him my silent thanks. The list goes on and on and includes

the names of men and women from all parts of the globe.

However what has been lost in the reaches of time is the story of

who inspired Aime Tschiffely to climb into the saddle!

It may come as a surprise to my fellow Long Riders to discover that

the main root of modern equestrian travel is Russian.

In 1875 Count Zoubovitch of Hungary rode 800 miles from Vienna,

Austria to Paris, France. His journey was done in such record time

that few believed it would be possible to ever travel faster on

horseback.

Then in 1889 Mikhail Vasilievitch Aseev made headlines. The famed

Cossack horseman rode 2,200 miles, from Kiev, Russia to Paris, France,

in the breath-taking time of 33 days! Using two cavalry mares named

Diana and Vlaga, Aseev averaged 100 kilometers a day in his mad

dash across Europe.

|

|

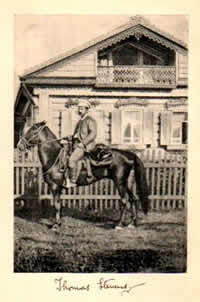

Famed

Russian Cossack Mikhail Vasilievitch Aseev rode from Russia

to Paris in only 33 days! |

Yet

it was an age of centaurs.

Aseev's record was almost instantly dashed to pieces under the iron

hooves of Dmitry Peshkov's horse.

Like his fellow Cossack, Peshkov was born for one purpose in life,

to ride horses. And like Aseev he was anxious to show a skeptical

world that the best horsemen on earth resided in Mother Russia.

Dmitry departed from the village of Albanzinski, Siberia in the

winter of 1889 and rode west. For 5,500 miles he and his pacer,

a gray named Seriy, pounded across the frozen steppes. They reached

St. Petersburg in 193 days after averaging more than 28 miles a

day. A hero's reception with the Czar awaited the Cossack and his

still fresh horse.

And here our story takes an unexpected foreign turn.

An American newspaperman, Thomas Stevens, had been ordered by his

New York editor to ride across Russia and report back on what he

saw.

What he saw was Peshkov!

It

was intrepid American reporter, Thomas Stevens, who rode across

Russia and told the world the story of Dmitry Peshkov

It

was intrepid American reporter, Thomas Stevens, who rode across

Russia and told the world the story of Dmitry Peshkov |

Tearing

across the steppes towards the unsuspecting reporter came a

little man and his fast moving horse.

"The Cossack turned out to be a small, wiry man, twenty-seven

years old, with a pleasant face of almost mahogany darkness

from the long exposure of the wintry winds of Siberia. His horse

was a big-barreled, stocky gray pony about fourteen hands high.

The horse was well chosen for his task. He was all barrel, hams,

and shoulders. His pace was a fast, ambling walk that carried

him over the ground at five miles an hour and left the big chargers

of the Czar's honor guard far to the rear."

Dmitry and Seriy had no way of knowing that together they were

about to ride into the history books, at least for a while.

Stevens did report back to his boss.

A news story did run in New York.

But what had more lasting consequences was the book Stevens

wrote soon after. Entitled "Across Russia on a Mustang"

it gives us a peek into a Russia that is no more. Serfs and

Czars compete on the pages for Stevens's attention. But through

it all comes riding Dmitry Peshkov.

The book was an instant hit in the United States, England, and

more importantly, Canada.

For that is where Roger Pocock lived. |

An exiled Englishman, and former member of the Royal Canadian Mounted

Police, Pocock was always eager for a taste of danger. He decided

to dine therefore on the hardships of the infamous Outlaw Trail!

"Knowing that Peshkov's record for travel on a road will remain

unrivaled, I set about to make another standard - that of horsemanship

and scouting over difficult ground."

This Long Rider saddled up in 1891 at Fort MacLeod, Canada and headed

south into an equestrian challenge that even he could not have foreseen.

He rode 3,600 miles through the most infamous and bandit-ridden

portion of the American West. What has now passed into historical

legend, the Wild Bunch at Robber's Roost, the outlaws of Hole in

the Wall, the desolate beauty of Brown's Park, Pocock not only saw

but crossed unscathed on his milk-white Arab gelding.

Roger

Pocock had already been a soldier of fortune and cowboy, when

he made his 3,600 mile equestrian odyssey down the entire

length of The Outlaw Trail

Roger

Pocock had already been a soldier of fortune and cowboy, when

he made his 3,600 mile equestrian odyssey down the entire

length of The Outlaw Trail |

"Where

are you from," one outlaw asked him?

"England," he answered humbly.

"England? Is that a fort?"

Yes, Pocock saw the last of the real west.

His adventures however were captured in a best selling book

called "Following the Frontier."

It sold like hotcakes in the United States, even up in the rainy

depths of the state of Washington. George Beck lived there,

a long way from the Utah deserts that Pocock described, and

even further from the beloved steppes of Dmitry Peshkov. |

They

were the most well-traveled equestrian team in the twentieth

century, covering 20,352 miles. Yet George Beck, and his faithful

Morab gelding Pinto, both came to a tragic end.

They

were the most well-traveled equestrian team in the twentieth

century, covering 20,352 miles. Yet George Beck, and his faithful

Morab gelding Pinto, both came to a tragic end. |

Beck was a lumberjack and no horseman.

But he dreamed of making the longest continual ride in modern

history.

He did it.

Sadly his remarkable feat is now all but forgotten.

Setting off in 1912 from the village of Shelton, Washington,

Beck and three companions headed off to visit the capitals of

all lower 48 states. More than three years, and 20,352 continuous

miles later, the four weary Long Riders rode into San Francisco.

They expected to be hailed as heroes.

Instead an Irish cop told them to "get them hayburners

off the street."

Beck and his companions weren't just disappointed.

They were broke.

They sold all their horses and saddles, except Pinto. He was

the Morab gelding who had traveled with them every step of the

way. While his three companions rode the rails like hobos back

towards Seattle, Beck used the last of their money to ship him

and faithful Pinto home on a tramp steamer.

He tried several times to interest book publishers in his and

Pinto's story but had no luck.

|

"I wrote it sweet enough but the deal came up sour," he

said.

Beck died dead drunk and broken hearted in a ditch, drowned in six

inches of muddy water. With his master dead, Pinto was shipped off

to the rain soaked depths of the Olympic Rain Forest. The greatest

equestrian travel legend of the 20th century passed his last days

working as a forgotten packhorse.

Beck's death seemed to prove that the world was looking in a new

direction, towards the new-fangled automobile. No one was interested

any more in a horseman's dusty story, no one except a tough kid

from Switzerland.

His name was Aime Tschiffely and he was hungry for adventure.

Aime left his village near Lake Biel at an early age to see the

world no matter what it cost. Thus he had few talents to recommend

him when he landed in England in 1915. At first he made his living

as a circus fighter, taking on all comers for the sake of a few

dollars. But he was smart, so he soon talked his way into a job

teaching at a plush boy's school in Argentina.

Before leaving London he became a fan of adventure travel stories.

He would have learned about Beck's record breaking trip through

America from the British press. He would have read the best selling

account of Pocock's adventurous ride among the outlaws. He undoubtedly

knew about Peshkov's legendary journey across the frozen wastes

of Russia.

Ten years later, with the knowledge of these other equestrian legends

behind him, Tschiffely set out to ride from Argentina to Washington

DC.

It was a mythical trip that almost never came to be.

With no prior equestrian experience to fall back on, the 29-year-old

Tschiffely ignored the legions of local Argentine critics who told

him his quest to ride 10,000 miles was impossible and absurd.

Not only did this brash neophyte propose to attempt this equestrian

odyssey, he said he was going to do it on two elderly horses, ages

15 and 16, owned by a Patagonian Indian.

In his own words, "They were the wildest of the wild."

But if Tschiffely, who had only recently learned to ride, barely

knew the difference between a hackamore and a halter, at least he

knew his history. In his bones ran a genetic impression that whispered

to him of star filled nights and wind-borne freedom.

Somewhere deep in his soul Aime knew that though he proposed to

ride into the unknown, others had ridden there before.

Of course history has proved Aime right.

His book changed the course of equestrian travel history.

We can look back now from the luxury of our computer driven world

and see how everything, and nothing, has changed in the seventy-five

years since Aime stepped up onto the back of his wild horse.

For six thousand years each generation of mankind has been supremely

confident, arrogant in the reoccurring belief that theirs is the

ultimate expression of the human experience. Meanwhile the horsemen

and women of history have watched from the sidelines while fires

were lit, wheels were invented, pyramids were built, railroad lines

were laid, automobiles were driven, and computer screens were peered

into.

Through out this vast never-ending stream of human experience and

effort one thing has run through our collective unconsciousness,

the need for terrestrial freedom.

Six thousand years after Epona first grabbed a handful of mane and

swung on board that wild forest pony, we, her grandchildren, still

dream of imitating her bold move.

We long for the blood stirring sound of horse's hooves pounding

across the steppe.

We long for the sweet smell of the leather saddle that takes us

to adventure.

We long for the feel of the gentle rain in our face, the hot sun

on our back, and a happy horse between our legs.

And most of all, like Aime, and George, and Roger, and Dmitry, and

Mikael, and all those other forgotten equestrian heroes and heroines,

we long for our eyes to be filled with the sight of a wide, free

horizon.

Peshkov |

For

6000 years that altar of travel, the saddle, has been calling

some of us to roam the world, like Dmitry Peshkov.

So what's stopping you?

For that is what we Long Riders are, and this pathetic attempt

at story telling is what we are about.

See you on the trail, Saddle Pals.

CuChullaine |

|

CuChullaine

O'Reilly

|

CuChullaine

O'Reilly, a.k.a. Asadullah Khan, has been described as "an

exile and traveler who is no longer entirely American."

After extensive travels in Afghanistan, CuChullaine converted

to Islam and journeyed to the Muslim holy city of Mecca. He

taught journalism for Boston University to Afghan guerrilla

fighters resisting Soviet invaders and was marked for assassination

by KHAD, the Afghan communist secret police, for his work with

the mujahadeen resistance groups.

CuChullaine has spent more than twenty years studying equestrian

travel techniques on four continents. He made lengthy trips

by horseback across Afghanistan and Pakistan before leading

the Karakorum Equestrian Expedition through five mountain ranges,

including the Himalayas, and traversing the Diamer Desert, thereby

setting the record for the longest recorded horseback ride in

Pakistan's history. CuChullaine was thereafter made a Fellow

of the Royal Geographical Society. |

He is one of the Founding Members of The Long Riders' Guild, the

world's first international association of equestrian explorers.

CuChullaine is the author of "Khyber Knights", the thrilling

tale of his adventures in Pakistan, and "The Long Riders,"

the world's first equestrian travel anthology. He is married to

Basha Cornwall-Legh, the Anglo-Swiss equestrian explorer.

"Tschiffely's Ride" by Aime Tschiffely, "Across Russia

on a Mustang" by Thomas Stevens, "Following the Frontier"

by Roger Pocock and "Khyber Knights" by CuChullaine O'Reilly

are part of the world's largest collection of Equestrian Travel

titles. These books are featured at http://www.horsetravelbooks.com/

or can be ordered from your local bookstore..

For

more information about the world's first international association

of equestrian explorers and long distance travelers, of which CuChullaine

O'Reilly is one of the Founding Members, please visit The Long Riders'

Guild at http://www.thelongridersguild.com/.

.

|