The Red and the

White

By Alexander Repiev

The Cossacks have made Russia.

– Leo Tolstoy |

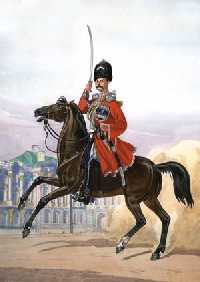

An officer of His Majesty’s Life Guards,

wearing a red cherkeska. |

The left arm was aching. Dennis rubbed it

gently and looked slowly up. His eyes, after a sleepless night, were aching

too. They painfully took in the horses. Golden Dons, dark Kabardins, gray

Arabians and Tersks. Nearly 2000 mares grazing peacefully, with their foals

prancing nervously around. When the explosions were especially disturbing to

the mares, they would freeze and prick up their ears. When a German plane

buzzed over the stud, some of the mares neighed faintly calling up their young.

It was July of 1942. The Germans were rushing

to the Caucasus, lured by Caspian oil. The Red Army was putting up some

disorderly resistance, buying some time. The horses had been hastily collected

from several studs to be taken away as soon as possible in order not to be

captured by the enemy.

The arm was aching. His mind fogged, he

distractedly gazed at the ugly scar… Ivan… where’s he now, his

ol’ pal Ivan? In Turkey, perhaps… or in France… if he managed to

catch the last ship at Novorossiisk in 1920, with the other Whites.

…They clashed on a fine sunny day in 1919

not far from Ekaterinodar, in the Kuban steppe. The White Cossacks and the Red

Cossacks, all masters of skirmishes and raids, second to none in head-on saber

combat, all seasoned formidable fighters trained from the cradle to ride like

gods and to fight like gods… with both hands, with jighitovka

tricks, with Asiatic ruses, and with the dashing valor passed on from

generation to generation of that race of warriors. There was no match to them

in horseback warfare, but… they were all Cossacks, on either side.

Cossacks against Cossacks! Brother against brother, son against father!

The battle was a vision of hell unleashed on

earth, atrocious and intoxicating. Hundreds of hoofs pounding, hundreds of

sabers swishing, hundreds of throats whining and howling. And that petrifying

and hair-raising and blood-curdling sound, the clang of steel hitting steel.

Good, tempered, blood-thirsty steel.

Wild with fighting madness, his hat and

scabbard lost and his right shoulder bleeding, Dennis was cutting, stabbing and

parrying automatically, the old family Caucasian saber in the right hand and a

revolver in the left. His horse, his old battle friend, knew his business,

responding to commands given by legs and body.

A gun pointed at him, a slug ricocheting from

the metal pommel and hitting the neck of his horse. Dive and shoot from under

the horse’s belly. Back into the saddle, just in time to look into the

distorted bearded face of a huge Don Cossack. A blow sending a numbing shock up

his arm. Thrust the blade down and then, an old family trick, jerk it abruptly

counterclockwise to knock the opponent’s saber out to dangle on the

sword-knot for a moment. A moment is enough.

And strike, strike, strike.

…And, then he saw Ivan. For the first time

in years. Since the Civil War had split Russia, Dennis was searching for his

friend. And now he found him, at last, in the uniform of a colonel of His

Majesty’s Cossack Life Guards, the crème de la crème of

Cossacks, the envy of every Cossack youngster.

Their frenzy ebbing, they stared at each other,

both re-living in a few moments the long years of friendship, mock rivalry in

racing and jighitivka horseback trick exercises, fighting back to back

in village brawls, sharing first love experiences, till Ivan, an ataman’s

son, went to Novocherkassk to join the Cossack Cadet Corps. Stunned, Dennis did

not see the lightning that hit his left arm. The last he saw of was the horror

in Ivan’s beautiful blue eyes. Ivan, Ivan.

… The Gypsy herdsman was running like mad

howling banshees. What?! Impossible! To slaughter the horses? Bastards! They

said they would send a cavalry company to drive the huge herd away beyond the

Caucasian Ridge. Bastards! To massacre hundreds of the finest horses, to

destroy the pride of the Steppe! The Gypsy was sobbing.

It was an order, he had to obey. But he could

not! In a stupor, tears blurring everything, he put his hands on the trigger of

a battered Maxim machine gun. He closed his eyes and was about to pull the

trigger when he heard a distant sound. Thank god! They are coming, the company

promised to him by the NKDV officer. He lost consciousness for a moment.

When he came to, his sore eyes discerned in

front of him a horseman in full dress uniform of the Cossack Guards. He shut

his eyes trying to shake off the ghost; when he reopened his eyes his vision

cleared, but the ghost was still there. And… the ghost looked like Ivan,

his pitch-dark beard slightly grayed. It was Ivan all right, of all the people.

Now Dennis could even make out St. George crosses, four of them, on a

snow-white cherkeska, and a dagger and a saber engraved with silver.

Dennis gasped in admiration of so much of forgotten Cossack splendor. Several

old Cossacks and youngsters were moving in the background.

The horsemen rushed to the ammunition boxes

stuffing cartridges into their saddlebags. In a moment the herd swung into

motion with the young men galloping and cheering ahead and the elders winding

behind. Dennis had neither time nor desire to ask where Ivan had come from,

where he had been hiding all those long years. They cantered along side by side

in dead silence.

Next day, when they were near the Burghustan

plateau they felt pursuit. The outriders reported that German Edelweiss

mountain troopers were riding in armored vehicles having a very hard time

negotiating narrow paths. Several of the old warriors stayed behind to ambush

their pursuers. When they caught up with the herd, hardly a word was said. One

of them had a captured German machine gun slung over his shoulder.

About two days to reach the Cross Pass over the

Main Caucasian Ridge. Beyond it was Georgia, and relative safety. That night

they slowed down a bit, the riders dozing away in their saddles. Dinner was

some bread and cheese and some horse milk to wash it down with. A minute to

switch the saddle onto a spare horse, and on. ON! The next day they had to

shoot several exhausted and injured foals.

The sun was setting on another long day, the

heard was approaching the Burghustan ridge, its white cliffs within a mile.

Then they saw them, or rather heard them. German troopers chasing them on

horseback. The lead mares were about to step onto the winding paths that would

bring them down beyond the ridge and into a valley. It was a wide valley, too

wide a valley. If the Germans got on the top of the ridge while the herd were

still crossing the stream and the valley, the Cossacks would be easy targets.

The Edelweiss troopers could sit on the ridge and take their aim at leisure,

like at a shooting range.

As the herd descended into the valley, the

young Cossacks were cracking their whips wildly, trying hard to contain their

tears. At the rear of the herd, the saddled horses of their grandfathers were

trotting nervously. Their stirrups were neatly tucked up, and old sabers and

cherkeskas, the noble battle dress of the Cossacks and Caucasians,

fastened to their saddles.

The eight old Cossacks were taking their time

and getting ready. They shared their little remaining ammunition and loaded

their short cavalry carbines. Each of them carefully prepared several positions

that commanded a good view of the path. One warrior stood ready with a huge

stone right above the path. They were damn good at those little tricks of

Asiatic mountain warfare.

When the pursuers appeared, an avalanche of

stones cut into their column hitting men and horses. Several horsemen were hit

by the Cossacks’ gunfire. The Germans at the tail rushed forward looking

for shelter as they fought back. Heavily outnumbered and short of ammunition,

the Cossacks had no chance. Yet, they could not retreat. The Edelweiss were

good, they were part of the German elite forces, and they knew how to fight in

the mountains. An hour later the shooting stopped.

When the shooting had broken out, the herd

bolted and the front end rushed into the mouth of a gorge on the other side of

the valley. As darkness fell the heard was safely into the huge canyon several

miles away, on the way to the pass.

On the morrow the women from the

Burghustanskaya stanitsa (Cossack village) came to the slopes. The

German corpses had already been removed. The women searched for the dead

Cossacks to bury them properly. There among the dead they found Dennis and

Ivan.

They were lying side by side. Dennis was

hugging the earth, Ivan was clutching a bloodstained dagger in his hand. The

friends. The enemies. The Red and the White.

|